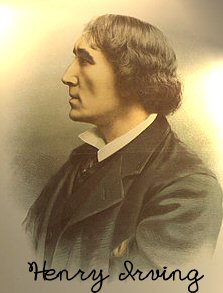

By Henry IRVING.

MANY years ago (I think it was in the autumn of 1858), I made an ambitious appeal to the public which I don’t suppose anybody remembers but myself. I had at that time been about two years upon the stage, and was fulfilling my first engagement at Edinburgh. Like all young men, I was full of hope, and looked forward buoyantly to the time when I should leave the bottom rung of the ladder far below me. The weeks rolled on, however, and my name continued to occupy a useful but obscure position in the playbill, and nothing occurred to suggest to the manager the propriety of doubling my salary, although he took care to assure me that I was “made to rise.” It may be mentioned that I was then receiving thirty shillings per week, which was the usual remuneration for what is termed “juvenile lead.”

At last a brilliant idea occurred to me. It happened to be vacation time — “preaching week,” as it is called in Scotland — and it struck me that I might turn my leisure to account by giving a leading. I imparted this project to another member of the company, who entered into it with enthusiasm.He, too, was young and ambitious. It was the business aspect of the enterprise which fired his imagination, it was the artistic aim that excited mine.

When I promised him half the profits, but not before, he had a vision of the excited crowd surging round the doors, of his characteristic energy in keeping them back with one hand and taking the money with the other; and afterwards, of the bags of coin neatly tied and carefully accounted for, according to some admirable system of book-keeping by double entry. This was enough for me, and I appointed him to the very responsible position of manager, and we went about feeling a deep compassion for people whose fortunes were not, like ours, on the point of being made.

Having arranged all the financial details, we came to the secondary but inevitable

question — Where was the reading to be given? It would scarcely do in Edinburgh;

the public there had too many other matters to think about. Linlithgow was a likely

place. Nothing very exciting had occurred in Linlithgow since the Regent Murray was

shot by Hamilton of Bothwell Haugh. The old town was probably weary of that subject

now, and would be grateful to us for cutting out the Regent Murray with a much superior

sensation.

My friend the manager accordingly paid several visits to Linlithgow, engaged the Town Hall, ordered the posters, and came back every time full of confidence.

Meanwhile, I was absorbed in “The Lady of Lyons,” which, being the play that most

charmed the fancy of a young actor, I had decided to read; and day after day, perched on

Arthur’s Seat, I worked myself into a romantic fever, with which I had little doubt I should

inoculate the good people of Linlithgow.

The day came which was to make or mar us quite, and we arrived at Linlithgow in high spirits. I felt a thrill of pride at seeing my name for the first time in big capitals on the posters, which announced that at “eight o’clock precisely Mr. Henry Irving would read ‘The Lady of Lyons.’ This was highly satisfactory, and gave us an excellent appetite for a frugal tea. At the hotel we eagerly questioned our waiter as to the probability of there being a great rush. He pondered some time, as if calculating the number of people who had personally assured him of their determination to be present; but we could get no other answer out of him than “Nane can tell.” Did he think there would be fifty people there? “Nane can tell.” Did he think that the throng would be so great that the Provost would have to be summoned to keep order? Even this audacious proposition did not induce him to commit himself, and we were left to infer that, in his opinion, it was not at all unlikely.

Eight o’clock drew near, and we sallied out to survey the scene of operations. The crowd had not yet begun to collect in front of the Town Hall, and the man who had undertaken to be there with the key was not visible. As it was getting late, and we were afraid of keeping the public waiting in the chill air, we went in search of the doorkeeper. He was quietly reposing in the bosom of his family, and to our remonstrance replied,”Ou, ay, the reading! I forgot all aboot it.” This was not inspiriting, but we put it down to harmless ignorance. It was not to be expected that a man who looked after the Town Hall key would feel much interest in “The Lady of Lyons.”

The door was opened, the gas was lighted, and my manager made the most elaborate –

preparations for taking the money. He had even provided himself with change, in case

some opulent citizen of Linlithgow should come with nothing less than a sovereign.

While he was thus energetically applying himself to business, I was strolling like a

casual spectator on the other side of the street, taking some last feverish glances at the play, and anxiously watching for the first symptoms of “the rush.”

The time wore on. The town clock struck eight, and still there was no sign of “the rush.” The manager mournfully counted and recounted the change for that sovereign. Half-past eight, and not a soul to be seen — not even a small boy! It was clear that nobody intended to come, and that the Regent Murray was to have the best of it after all. I could not read “The Lady of Lyons” to an audience consisting of the manager, with a face as long as two tragedies, so there was nothing for it but to beat a retreat. No one came out even to witness our discomfiture. Linlitligow could not have taken the trouble to study the posters, which now seemed such horrid mockeries in our eyes. I don’t think either of us could for some time afterwards read any announcement concerning “eight o’clock precisely” without emotion.

We managed to scrape together enough money to pay the expenses, which operation was a sore trial to my speculative manager, and a pretty. severe tax upon the emoluments of the “juvenile lead.” As for Linlithgow, we voted it a dull place, still wrapped in mediaeval slumber, and therefore insensible to the charms of the poetic drama, and to youthful aspirations after glory. We returned to Edinburgh the same night, and on the journey, by way of showing that I was not at all cast down, I favoured my manager with selections from the play, which he good-humouredly tolerated, though there was a sadness in his smile which touched my sensitive mind with compassion.

This incident was vividly revived last year, as I passed through Linlithgow on my way from Edinburgh to Glasgow, in which cities I gave, in conjunction with my friend Toole, two readings on behalf of the sufferers by the bank failure, which produced a large sum of money. My companion in the Linlithgow expedition was Mr. Edward Saker —now one of the most popular managers in the provinces.

1880